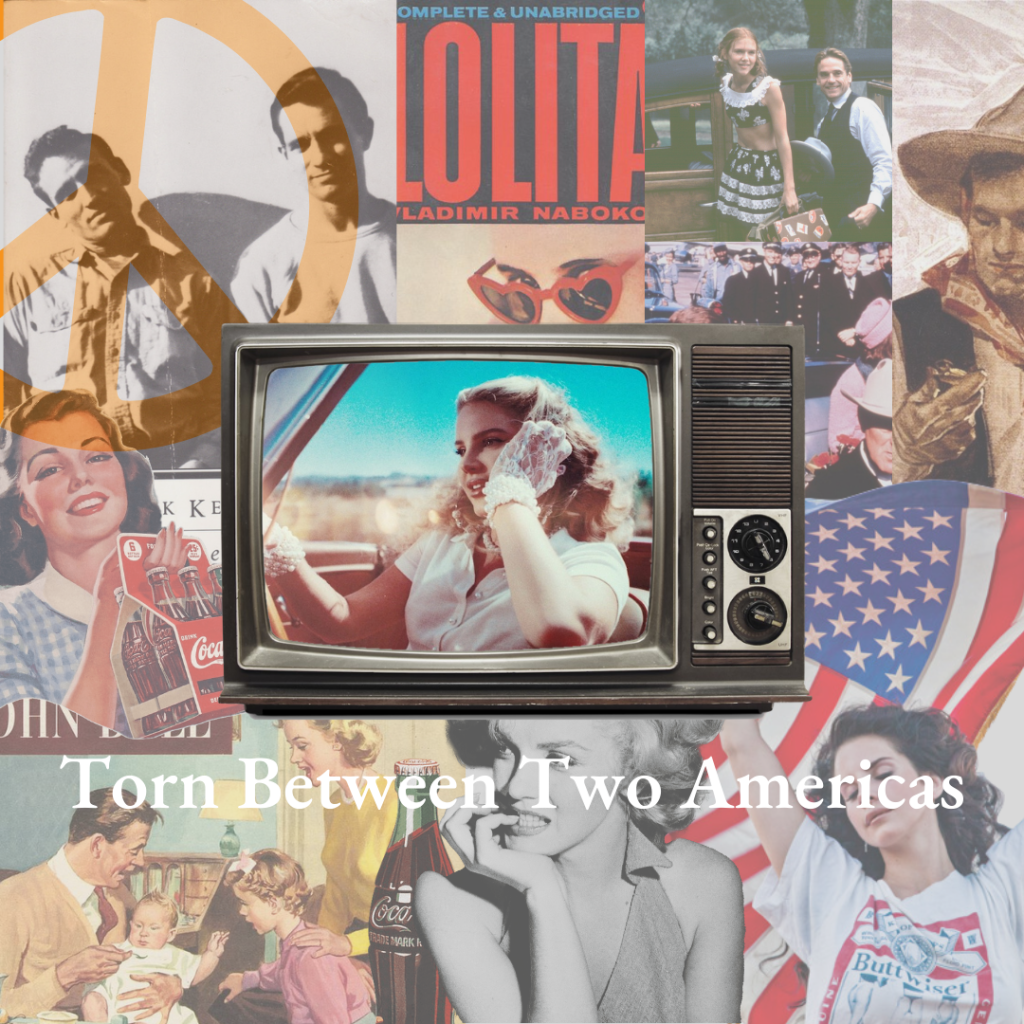

Exploring the Recent Thematic Shift in Lana Del Rey’s Oeuvre, the American Road Trip & the Female Experience in ‘Blue Banisters’

Part One

The Next Best American Road Trip?

The Next Best American Record.

Life is but a road trip for our beloved wordsmith of melancholy, Lana Del Rey. With its sharp twists and turns, abrupt halts and series of stopovers, life on the road is by every means representative of the course of life. Lana may stop and dwell somewhere for as long as she desires, meet, make love and memories with like-minded, explosive individuals—vagabonds who seek refuge in kind strangers as they share the same lifeblood—but once the thrill wears off, she will hit the road again to find the next high, the next authentic experience worth living for. In fact, this more or less captures the plot of her 2012 masterpiece, “Ride”.

The road trip as a metaphor for the course of life is evident from the omnipresent symbol of the truck as seen in Del Rey’s album covers. As a result, each album serves as a landmark, a brief departure from life on the road, as if to say, ‘at this point in my life, this is where I am right now, both physically and emotionally’. To put it more romantically, every album is a stopover which she shares with us, her fans, the strangers who share the same sorrows and hopeless ideals towards life. The dreamers.

The symbol of the truck alludes to the concept of the American road trip; an act of desperation to reclaim the freedom promised by the American dream; the search for meaning and purpose via authentic experience which can only be so rewarding before some order must be restored in an unconventional lifestyle. Hence, the road trip becomes an act of escape from responsibility and the conventional, neither of which suit the temperament of the human spirit but the road. The road trip as a metaphor for Lana’s lived experience—or rather, romanticised lived experience—is crucial as it underpins her work and philosophy on human nature.

This is not to be mistaken as a philosophy for how we should live our lives. This is frequently a subject of misunderstanding, breeding reproval from critics. It is the contrast between human desire, specifically, its destructive quality (how we can become slaves to our passions via desire-driven decision-making and its perilous ramifications, e.g., a poor choice in a partner) and the mundane that assures our viability, that Lana captures so eloquently, and which underpins her oeuvre.

How we should live our lives is not an answer that Lana provides us with. She merely captures human nature via the lens of the female experience in its most vulnerable form and instead asks—or rather, screams into the desolate wilderness of the great American plains—how and where the pursuit of happiness fits into the equation: ‘in the midst of the conflicting temperaments that reside within me, how am I to ever live a fulfilling life?’ This is very reminiscent of her famous lyric: “I’ve got a war in my mind”.

So you can see why it saddens me when her work is simply dismissed as the glamorization of destitution and abuse.

The concept of the American road trip is not unique to Lana Del Rey. The road trip genre in literature and film is often characterised by individuals who, sapped by the conventions of normalcy and itching for authentic experience, set out on a journey and return as changed individuals shaped by their countercultural exploits. They often bring home with them the crushing realisation—or awakening—that seeking true freedom, though thrilling, is unsustainable.

The post-war generation—the beatniks, the hippies—were all fond of life on the road as it was exhilarating, a means to free oneself from the weight of fear and uncertainty during World War II. Honouring their newfound freedom as the first generation that did not need to go to war, they hastily turned to moral obscenity: “their hedonistic search for release or fulfilment through drink, sex, drugs and jazz becomes an exploration of personal freedom, a test of the limits of the American dream” (Kerouac & Penguin Books, 2011). In reality, it only satiated the desire to transcend social constraints; only a temporary fix for a greater problem, that is, an overwhelming lack of meaning post-war. Jack Kerouac’s 1957 novel On the Road (1957) is a quintessential text of this era as it prompted many youths to seek pleasure as a reminder that we are free.

Similarly, Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita—predating the aforementioned literature by two years—raises a similar problem as Humbert, who eventually possesses Dolores Haze, is on a perpetual road trip with her. The illicit nature of his ‘relationship’, or rather, his sexual perversion, condemns him to a perpetual road trip. I don’t use the term ‘relationship’ to imply a mutual, romantic relationship, but rather, I use the term for its basic definition, “the way [in which] two or more people are connected” (Cambridge University Press, 2008). The road is, unsettlingly, both freeing and oppressive for Humbert because only on the road can he pursue the relationship—the road guarantees endless escape—but he is perpetually on the run from the law for what he is doing is wrong.

The road is for those who don’t fit in. Only on the road can you be free, dangerously void of all moral consequences. This reiterates the notion of the road as symbolic of life in its most liberated form, removed from all rules and regulation. To summarise, the road trip is a journey with no solid destination, alluding to nihilism, the only true meaning being sought in the journey itself.

Lana Del Rey’s exploration of chaos and order via the metaphor of the road trip is undoubtedly evocative and possesses literary depth for mere indie music, but in recent years the exploration itself has noticeably shifted. Notice the absence of the truck in the album cover for “NFR!” which instead depicts Lana on a boat, against turbulent seas, clinging to ‘her man’ to stay afloat (typical of our melodramatic queen). The pivotal transition from truck to boat to the gathering at the country club and finally, home with her dogs Tex and Mex, is not to be glossed over. It is intentional. If the recurring symbol of the truck was utilised throughout her discography, its gradual erasure must indicate a pivotal shift in her view of life or life circumstances.

So what prompted this shift and what does it mean? The truck as a metaphor has remained a known fact amongst die-hard Lana fans so it is prudent to embark on this enquiry—this journey if you will—into the cause of this shift. It is only after listening to “Blue Banisters” that the ‘veering off the road’ began to make sense to me. I couldn’t see why, or rather, I didn’t think much of the transition during the release of “NFR!” or “Chemtrails” but “Blue Banisters” completed my understanding.

Part Two

Turbulent Seas

There is something about “NFR!” that has earned the unique admiration of Lana Del Rey fans. It is different, but how precisely? I believe it’s because it’s a transitional album.

We find our first hint of political themes in Lana’s work in NFR!’s ‘The greatest’ wherein Lana sings:

Hawaii just missed a fireball

L.A. is in flames, it’s gettin’ hot

Kanye West is blond and gone

“Life on Mars” ain’t just a song

Oh, the livestream’s almost on

Within the backdrop of soft piano and mellow guitar towards the end of ‘The greatest’, Lana makes reference to the meteor spotted in Hawaii in the summer of 2019, the L.A. forest fires as a result of global warming, Kanye West’s ‘conversion’ to conservatism and support for Trump, whilst underlining the absurdity of it all via the “Life on Mars” Bowie reference. She hints at censorship as evident from the final line where Lana stops singing about socio-political issues once “the livestream’s almost on.” Not only is Lana concerned about the farcical state of American politics and government inaction in the face of rapid climate change, but also about the loss of ‘the culture’. Even more so than politics, it’s the lack of empathy and understanding between individuals that Lana highlights; we view others as agents of political dogma before viewing them as people with a story. Lana laments the loss of popular culture and how it has dissolved into radical political correctness which inhibits artistic freedom. Cancel culture breeds fear in what one can say and do (hence the livestream reference), inhibiting our freedom of speech and expression. Lana laments an America that she doesn’t recognise anymore, riddled by guilt, a stifling culture where we have inserted political discourse into every facet of life.

Lana’s ‘The greatest’ is certainly a turning point—one as courageous as manoeuvring a ship against turbulent seas—provoked by burnout from a ‘hedonistic indulgence of the culture’. Perhaps this claim is too harsh or an oversimplification. A more nuanced reading would perhaps be, ‘burnout from a culture that gives nothing in return for all the love that you give it’ (reminiscent of her poem, ‘L.A. Who Am I to Love You?’). And that’s where Chemtrails presents itself. Lana has given up on the culture that she once sought refuge in and finds herself coming back to whatever she can call home; her girlfriends, their partners, their kids, all down at the Country Club.

Lana’s earlier work constitutes Americana glamour reminiscent of the popular culture (e.g. Hollywood), her work now is reminiscent of ‘real’ country Americana. The single theme that unites the old and the new is the notion that freedom comes with a price, and that price is the deep-seated knowledge that we can never transcend our humane desires, and hence, no matter who you are, how wealthy, poor, inept or talented, you’re never going to be completely satisfied because we are burdened by striving for ideals when we ourselves are inherently flawed. We possess a natural affinity for fantasy, which knows no bounds, yet are not void of moral consequences ourselves. The equilibrium between good and evil, of highs and lows, remains an inseparable feature of the human experience. Notice how Lana’s 2012 single ‘Ride’ concerns an on-the-road vagabond who removes herself from the American dream because it’s perfectly useless to venture into the corporate rat race if it will leave you just as helpless and destitute in your personal life, and how in ‘National Anthem’ she emulates the first lady, proudly proclaims that “Money is the anthem of success… Money is the reason we exist” before she loses her husband to the assassination. ‘Ride’ and ‘National Anthem’, both released in the same era, are really two sides of the same coin, or should I say, two sides of the same America.

In her recent work, Del Rey departs from her usual formula—first the Americana fantasy and glamour of evil, then the painful acknowledgement of its intangibility and finally, the indissoluble melancholy that ensues—and instead sets foot into new territory. After giving up ‘the culture’ she seeks culture in the rural life embedded in American tradition: the ranch, the great plains, the country club, the cowboys and the nuclear family. In her monologue in ‘Ride’, she claims, “there’s no use in talking to people who have a home. They have no idea what it’s like to seek safety in other people—for home to be wherever you lay your head” (Grant, 2012). But now that we have lost ‘the culture’, the ability to trust, let alone find, like-minded, freedom craving individuals on the road, where and to whom do we turn? For Lana, it was her sisters, her girlfriends, their partners and their kids, all down at the Country Club.

Part Three

Home Is Where Half My Heart Is/

The Wandering Woman

“Chemtrails” and “Blue Banisters” still possess vivid, Americana imagery like her earlier work but instead of the motto, “Live fast, die young, be wild, and have fun”, it’s America through the lens of the flower-power wild child who lived longer than she had hoped or envisioned, past the youthful ages of lust, who lived through it all and now longs for stability.

As well as grappling with fame in her recent work, change is a new and recurring theme throughout Chemtrails, “Seasons may change—But we won’t change” she sings in ‘Yosemite’. She wants to settle down but she is still wild at heart and knows that women like her—thrill-seeking, people-loving and passionate—can’t ever really settle down unless they give up a fundamental part of their temperament. So she decides, she won’t change—quite literally “Lust for life”. More on change later.

In her single ‘Blue Banisters’ Lana departs from popular culture where she once sought meaning and turns to American home life where she is confronted by the reality that she longs to settle down but realises that a woman like her, ‘a muse’ cannot. Throughout the song, she attempts to fill a void as her sisters paint her banisters green and gray to integrate her back home but is confronted with the realisation that only a man can fill that void. It’s the story of a woman torn between the extremities of culture, torn between two Americas.

Blue Banisters Song Analysis

Vivid imagery opens Blue Banisters, evoking the essence of the American south: John Deere tractors reminiscent of agriculture—a back-to-basics lifestyle—and the nonchalance with which a beer is offered, a sign of hospitality and family.

There’s a picture on the wall

Of me on a John Deere

Jenny handed me a beer

Said, “How the hell did you get there?”

Oh, Oklahoma

Mm-mm, mm

Lana’s voice dwells on ‘Oklahoma’ as though she is recalling a sunken memory. Upon further research, I find that Lana’s ex-boyfriend/ex-fiancé Sean Larkin is a police officer who worked in the state.

There were flowers that were dry

Sittin’ on the dresser

She asked me where they’re from

I said, “A place I don’t remember”

Oh, Oklahoma (Oh-oh)

Repetition of ‘Oklahoma’ could suggest one of two things, though I am convinced it is the latter: Lana is desperately trying to recall the memories she made in Oklahoma or Lana still keeps the dried flowers from her ex-lover yet pretends not to remember where they are from, for the memory is now tainted with pain.

Jenny jumped into the pool

She was swimmin’ with Nikki Lane

She said, “Most men don’t want a woman With a legacy, it’s of age

“She said “You can’t be a muse and be happy, too

You can’t blacken the pages with Russian poetry

And be happy”

And that scared me ‘Cause I met a man who…

This seems self-explanatory yet is most crucial. Men are intimidated by women who are more financially successful and intelligent than themselves due to traditionally ingrained social norms; many men feel as though it harms or invalidates their masculinity. Finding love as a successful woman is hard. “You can’t be a muse and be happy too” is a line that particularly struck me as it transported me to Lana’s early music with her Hollywood sex symbol image in “Born to Die”. Lana embodied sultry old Hollywood and was hailed as an alternative music muse. It was during this era where songs about salacious relationships were abundant—a glamorous fantasy. With regards to craving stability and happiness, a muse figure belonged to no one but was loved by everyone (think Marilyn Monroe). Music in her “Born to Die” era often glamorised the power of female sexuality with its chaotic ramifications; the loss of innocence, lust obstructing logical thought, all of which eventually resulted in a pensive sadness for the persona of Lana Del Rey.

Said he’d come back every May

Just to help me if I’d paint my banisters blue

Blue banisters, ooh

Said he’d fix my weathervane

Give me children, take away my pain

And paint my banisters blue

My banisters blue

The shadow-like presence of the elusive ‘wandering man’ is embedded throughout the song and subsequently in the promotional video for the song. Confronted by the perplexities of navigating a viable relationship as a muse figure, she sings about a hypothetical relationship where she fulfils the role of of domestic woman—as if appraising the idea of putting down roots since she is considering staying for a prolonged period of time—and supposes that she would remain unsatisfied after all, for her character could only ever attract a wandering man, a partner as unconventional as herself.

If relationships are said to complete you, if your partner is your other half, then the figurative wandering man in Blue Banisters represents the other half of Lana’s heart that will always remain on the road, forever drifting (reminiscent of her song ‘Thunder’).

Although the vagabond lifestyle is not specific to males, leaving home to seek meaning is traditionally considered a male pursuit given that masculinity is traditionally associated strength and endurance, and women with beauty which connotes tenderness. Beauty is portrayed as a female virtue and oftentimes men may make up for a deficiency in physical appeal via other means such as wealth, status and/or power. Consider the many examples in film and television which depict couples comprised of attractive females and average-looking but conventionally successful males. Rarely do we find examples of the opposite. For a woman of her wit, Lana embodied the search for meaning in her art, a traditionally masculine pursuit, hence, she remains the wandering woman.

Ultimately, the presence of the wandering man is left ambiguous in the song—in real life however, the man in the promotional video is Clayton Johnson whom Lana was reportedly engaged to—which intimates that whether he is real or not, it wouldn’t make much difference as he would never be physically there to support her. For a woman of Lana’s caliber, a relationship is inevitably doomed in one way or another.

There’s a hole that’s in my heart

All my women try and heal

They’re doin’ a good job

Convincin’ me that it’s not real

It’s heat lightning, oh-oh-oh, oh

The hole is the man that’s missing in her life. Her ‘sisters’ are trying to convince her that she doesn’t need a man but she knows it’s not true and she longs for him.

‘Cause there’s a man that’s in my past

There’s a man that’s still right here

He’s real enough to touch

In my darkest nights, he’s shinin’

Ooh-ooh-ooh

[Pre-Chorus]

Jenny was smokin’ by the pool

We were writin’ with Nikki Lane

I said I’m scared of the Santa Clarita Fires

I wish that it would rain

I said the power of us three can bring absolutely anything

Except that one thing

The diamonds, the rust, and the rain

The thing that washes away the pain

But that’s okay, ’cause

Lana argues that despite “the power of us three”, referring to her friend Jen Stith, country singer Nikki Lane and herself as powerful, independent and accomplished women, still cannot ‘bring’ “the diamonds, the rust and the rain that washes away the pain”. This lyric alludes to the traditional role of men as providers and protectors of the family. Beautifully woven into the backdrop of the Santa Clarita Fires, the wildfire is representative of a yearning so strong that it burns exponentially, devouring you whole and reveals that only a man can be the metaphorical rain that ‘puts out’ this ache. To put it simply, the wildfire not only acts as a metaphor for the burning desire to settle down into home life, but also the contention that resides within her given the knowledge that though life on the road is a bygone lifestyle, home is not really for her either.

There are a few concurrent ideas at play here:

- As a free-spirited individual, Lana always seeks authenticity. The road epitomised freedom, only on the road could she share the unified burden of being human—a pensive, spiritual and psychological warfare within each individual—with other individuals who were also concerned with the inherent meaninglessness of life and the desire to transcend it through unconventional, artistic living. However, due to the loss of ‘the culture’, the road can no longer satiate her desire for escape because people have lost their authenticity and we can’t ever be free without authenticity and truth. Lana acknowledges that while she is still free-spirited, she must seek authenticity at home (exactly what you run from, you end up chasing) where her loved ones practice a culture that seems more conventional but are the only people left who truly love and understand her. It’s like a coming of age story about a girl who never wanted to grow up for she is young at heart.

- Regardless of the state of culture, Lana has always been aware that thrill-seeking on the road can’t last forever before it too grows old (order must be restored in a life of chaos because there is no highs without lows). Upon returning home she is confronted with and acknowledges the biological perspective that the female desire for stability and family grows with age.

- Despite her burning desire to settle down and transition into the next conventionally mature stage of her life, Lana is burdened by her enduring repute as a muse. Her success is burdensome in finding a male partner. A study conducted on the impact of intelligence on likeness of marriage revealed that a high IQ impeded a woman’s chances of getting married, with a 40% loss in marital prospects for every 16-point increase in IQ. Males on the other hand, saw their chances of getting married improve by 35% for every 16-point increase in IQ. Top-earning males were 8% more likely than their lower-earning counterparts to be married. (Cook, 2005). Why is this the case? Is it biology? The notion that the majority of men are innately more competitive than their female counterparts and hence desire power and control over the relationship? Or is it traditionally ingrained in social norms? I suspect it’s a bit of both.

- Ultimately, she grapples with feelings of displacement; the wisdom that though life on the road is a bygone epoch, home is where only half her heart resides; she no longer fits in with people on the road nor can she really belong at home and lead a traditional lifestyle—even though there’s a part of her who desires it—for she is a muse. Although I believe Lana has never been happier in her personal life, I believe it is this inevitable female struggle that she wishes to highlight.

And so, Lana is torn between two Americas: one which embraces conservative values with gross oversimplification (without nuance) and one which is too busy denigrating all constructs in the name of radical identity politics—constructs being the very pillars of culture–in a countercultural manner (again, without nuance or any regard for its implications).

Lana has been openly critical of modern-day feminism and her distaste towards it is perfectly valid. She believes women are powerful on their own but female desire for stability and family grows with age and this shouldn’t be a radical, anti-feminist concept, but one that is rooted in biology. Her indifference towards feminism also makes sense because her legacy—the search for meaning via art—deals with a fundamental human struggle via the female lens rather than it being an exclusive female struggle. For her, being female is a matter of coincidence, an ideal one at that, for I am convinced that only she can explore this subject with such depth and nuance.

“For me, the issue of feminism is just not an interesting concept… Whenever people bring up feminism, I’m like, God. I’m just not really that interested.”

– Lana Del Rey for an interview with The Fader Magazine, 2014

Now when weather turns to May

All my sisters come to paint my banisters green

My blue banisters grey

Tex and Mex are in the Bay

Chucky’s makin’ birthday cake

Jake is runnin’ barefeet,

there’s a baby on the way

And now my blue banisters are green and grey, ah-ah

Her sisters paint her banisters green to fill the hole in her heart; they can’t replicate the colour blue and the emotions of ‘sappy’ that her male partner would bring her but she settles for it nonetheless. Tex and Mex are her dogs, Chuck, her sister, is pregnant and Lana watches a new family grow whilst she has no such thing of her own. Grey could signify several things: a) they’ve stopped painting, meaning the sisters’ support can only go so far without a man, or b) that painting her banisters is getting old and she feels she’s getting old.

Summer comes, winter goes

Spring, I skip, God knows

Summer comes, winter goes

Spring, I sleep, Heaven knows

Every time it turns to May

All my sisters fly to me

To paint, paint

Spring is a transition season between the extremes of harsh winter and sizzling summer, where the snow thaws. She skips spring because the next transition stage of her life—having children/starting a family, doesn’t seem likely for her.

And perhaps this is why they said “Live fast, die young be wild and have fun” because lust doesn’t last forever and why live without it? This alludes to the notion of change and how Lana decides that though she has reached a transitional stage in her life where it’s time to move on from a life of lust, she is not willing to give it up for stability.

Chemtrails is about staying the same at heart and references change a lot:

Seasons may change

But we won’t change

– Yosemite, COTCC

We keep changing all the time

The best ones lost their minds

So I’m not gonna change

I’ll stay the same

– Dark But Just A Game, COTCC

Fin

Not All Those Who Wander Are Lost

Lana Del Rey and women alike are often ostracized from the 21st-century feminist movement. Women who audaciously but rightly acknowledge that they, though wild at heart, need men, family and some degree of stability to feel complete and that conflicting desires between establishing order and pursuing chaos is as biological as it is psychological. Lana Del Rey’s ‘Blue Banisters’ is an exploration of the two contrasting temperaments that reside within and define us via the lens of the female experience, which ultimately asks how and where the pursuit of happiness fits into the equation. Lana captures this universal struggle beautifully in Blue Banisters. We need more art about human desire in all its forms, whether it concerns the realm of lust and fantasy or our biological imperatives—for instance, today’s hyper-politicized world, removes the prospect of women later regretting not having children as a taboo, off-the-table discussion, and art which embraces the traditional instead of criticizing it, is seen as backward.

I believe Lana’s oeuvre is revealing and something ‘the culture’ can certainly learn from:

Lana prods at a few fundamental flaws of modernity and our radical attempts to denigrate social institutions due to a loss of meaning and identity in society. The pursuit of balance will undoubtedly remain a fundamental human struggle indissociable from the human experience. This is because we are burdened by striving for ideals when we ourselves are flawed—by ‘ideal’ I mean the desire to completely embody one of two extremes, chaos or order. Our current culture carelessly revels in extremes. On one end we have the nuclear family structure that needn’t be harmful—and can instead ensure the psychological wellbeing of all its members—but we carelessly passed down the practice without an explanation as to why we need tradition—we exaggerated biological differences between men and women and oppressed each party. As a result, many men feel as though an intelligent and successful partner would harm or invalidate their masculinity. On the other hand, we carelessly denigrate social constructs with no forethought—because the importance of tradition was poorly conveyed—or consideration that perhaps there is some element of truth in them. It doesn’t mean we should seek to eradicate constructs as a whole.

Similarly, as we grow unhappy with social injustice, we possess the desire to engage in extremities such as cancel culture. We jump to conclusions about an individual’s character on the basis of a belief they hold or held and pass judgement on people in an increasingly black and white manner in an attempt to build an ideal world where we eradicate hate. But we forget that life is not perfect, and in attempting to eradicate hate, we instead perpetuate more divide and hatred. In our rash attempts, we limit others’ free speech. We must find a middle ground.

We have forgotten that to be creative is to ask challenging and uncomfortable questions. To be human is to possess conflicting views. So communicate with each other, ask each other tough questions, seek to understand. Our idea of diversity is often limited to race, we need diversity of thought.

Even when it seems like the end, the end of culture, the end of humanity, Lana manages to derive new meaning. I wonder what she has in store for us next? As a free-spirited youth myself, I hope to see you on the road again Lana, whenever you’re back, whenever you’re ready.

Love,

blue skies and dragonflies

Sources

1. Bartleet, L. (2017). The truck in Lana Del Rey’s first four album covers: Born to Die, Ultraviolence, Honeymoon and Lust for Life. New Musical Express. Retrieved from https://www.nme.com/blogs/nme-blogs/lana-del-rey-artwork-theory-lust-2045441

2. Cambridge University Press. (2008). Relationship. In Cambridge Academic Content Dictionary (1st ed.). https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/relationship

3. Cook, M. (2005, January 23). Why brainy women stay single. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2005/jan/23/gender.comment.

4. Cooper, D. (2014, June 4). Cover Story: Lana Del Rey Is Anyone She Wants to Be. The Fader Jun/Jul 2014 Summer Music, (92). Retrieved from https://www.thefader.com/2014/06/04/cover-story-lana-del-rey-is-anyone-she-wants-to-be.

5. Delman, J. (2016, May 8). “Lolita” as an American Road Novel. Retrieved from https://medium.com/@superrrabbit/lolita-as-an-american-road-novel-6a2aa60af68d.

6. Kerouac, J., & Penguin Books. (2011). Blurb. In On the road. Penguin Books.

Leave a comment